The Three Mile Island, TMI Reactor accident

March 28, 1979

REFLECTIONS

OF A RESPONDER TO THE THREE MILE ISLAND ACCIDENT

TMI

about TMI, Too

Much Information about Three Mile Island

Presented at the National Radiological

Emergency Preparedness Conference

Sacramento, CA April 29, 2015

Why did I make this web page?

I was a member of the DOE Region 1

Radiological Assistance Team that responded to the accident at TMI in

1979. A friend who is still in the radiation response business thought

that the folks at the 2015, National Radiological Emergency

Preparedness Conference in Sacramento, would appreciate some of my stories and encouraged

me to pass them on. I hope that there is something to be gained from

reading the experiences of someone who responded to an actual serious reactor

accident even long after it occurred. Also, looking back, there was a lot

that was fun that happened while I was there, and I wanted to share those

experiences. And lastly, I have been retired for many years and the

meeting gave me the chance to get together with some folks who would now be

called on to respond if there was a similar problem today.

I have found that there are common elements

in emergency response of all kinds, whether as part the Red Cross, working with

people displaced by Superstorm Sandy; the local fire department, responding to

a fire or flood affecting our neighbors; or assisting police deal with a plot

by a fanatic armed with radioactive materials and explosives.

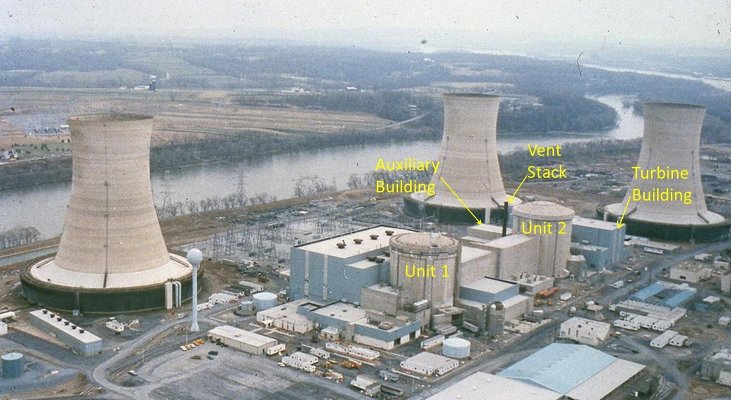

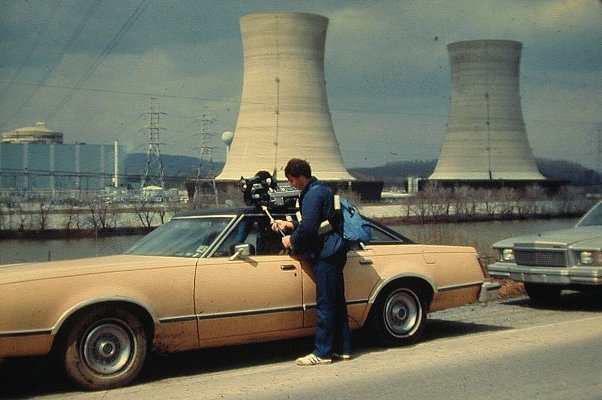

Unit 1 was down for maintenance. The

accident occurred in Unit 2. Behind it

and to the left is the auxiliary building and the vent stack that figure in the

accident.

Three Mile Island accident began about 4:00 AM on Wednesday March 28th, 1979. The plant's main feedwater pump tripped because of a problem while attempting to clear the demineralizers. With no coolant flow in the secondary loop the pressure started to rise on the primary side of the steam generator. The pilot operated relief valve (PORV) opened to relieve the pressure. These were normal, planned processes. None of this was known outside the Unit 2 control room. Like other DOE responders, I was blissfully ignorant, enjoying the last few hours of sleep I would get in the next 24.

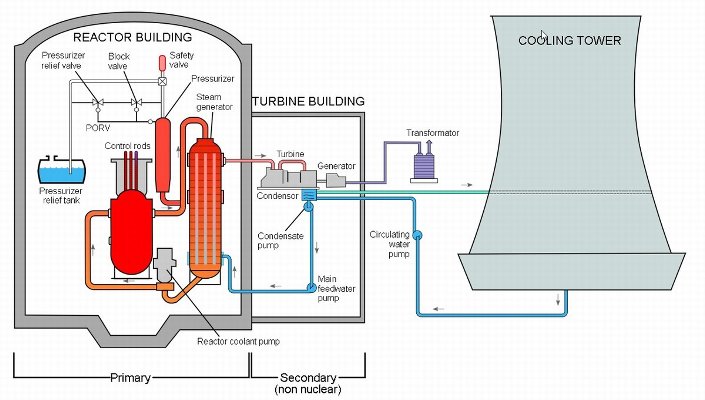

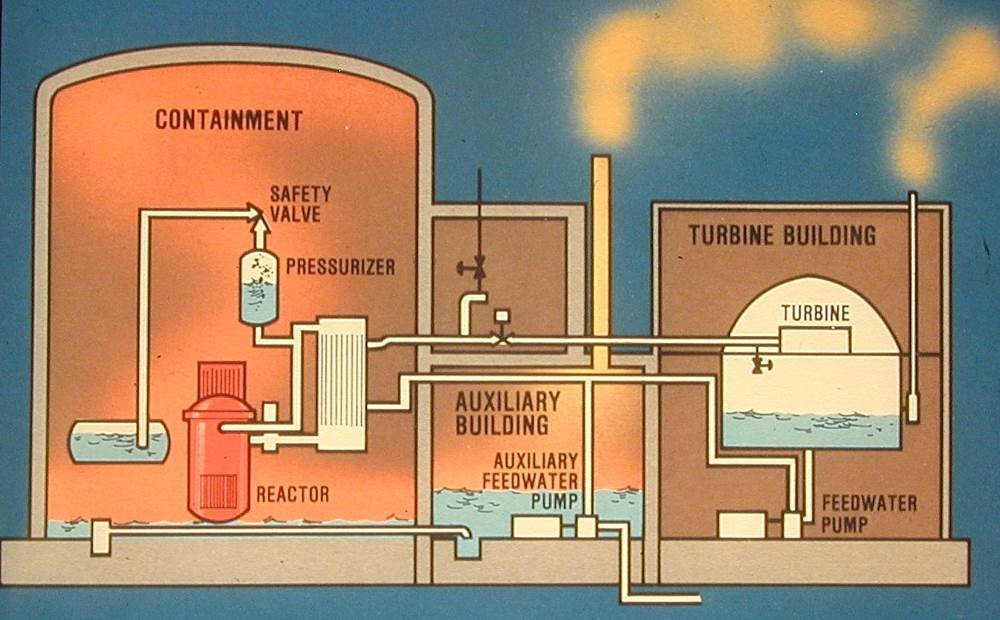

Schematic of a

Pressurized Water Reactor

The auxiliary feedwater

pumps, containment sump pump, auxiliary building, and the vent stack are

significant elements that are not shown in the diagram but come into play as

the accident progressed.

Within the first few

minutes one of the control room displays incorrectly showed that the PORV had

closed, so coolant continued to flow from the pressurizer. What that display actually showed was that power to the

solenoid controlling the valve was off. That would normally cause it to close,

but this time there was a mechanical problem causing it to stick in the open

position. The pressurizer relief tank overfilled,

burst its relief diaphragm, and primary coolant flowed to the containment sump.

From there it was pumped out of containment to the auxiliary building where the

gaseous fission products were released from the coolant to the building air and

then through the vent stack to the environment.

At this point there were

lots of alarms going off in the control room, but with no way to prioritize

them, the operators were focusing on the wrong ones.

The auxiliary feedwater

pumps started automatically but the coolant path was blocked by valves had been

closed during routine maintenance and had not been reopened when it was

completed. For the next several hours, operators continued to attempt to

control the situation but they did not prevent the core from being partially

uncovered, resulting in fuel being damaged. That

was not recognized until much later.

You now know more about the

accident than anyone did that morning.

At 6:56 AM a Site Area Emergency was

declared and Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency (PEMA) was notified.

They in turn notified Tom Gerusky and Maggie Reilly from the Pennsylvania

Bureau of Radiation Protection (BRP), other state and local agencies and the

Governor.

Within 15 minutes reactor staff at

Metropolitan Edison (Met Ed) called the Brookhaven National Lab

Radiological

Assistance Program (BNL RAP) hotline and told one of our team captains,

Tony

Greenhouse, that they had a reading of 600 rads/hr in the auxiliary

building.

For those who aren't familiar with radiation units that is enough to be

life threatening in less than an hour. They made it clear that

they were just informing us not requesting

assistance. Tony called our department chair, Charlie Meinhold,

to let

him know what was going on.

The BRP and BNL personnel had known

each other for some time. Charlie Meinhold and Tom Gerusky had been

graduate school classmates at the University of Rochester and worked together

at BNL before Tom moved to BRP. Maggie Reilly and I were Atomic Energy

Commission (AEC) Fellows under Meinhold at BNL. Tony Greenhouse had also been

an AEC fellow at BNL a couple of years before us. Tony, Maggie, and I had

been part of 6 week long study of environmental and population radiation dose

in the Marshall Islands just one year before.

It's

Important to know your team well and a trip to the South Pacific isn't a bad

way to do it.

From

the Marshall Islands trip

Maggie and Tony

on the right and I am on the left.

At 7:24AM a General Emergency was declared. At

BNL the RAP Team members were arriving,

being briefed, and gathering equipment. Dave Schweller the head

of the

Department of Energy, Brookhaven Area Office (DOE BAO) had been told

about the

RAP call and notified DOE Headquarters at Germantown, MD of a

"substantial" problem at TMI and recommended a RAP team response.

Bob

Friess, DOE BAO, alerted the Coast Guard requesting helicopter

transport to

Harrisburg for the BNL RAP team. Bob Bores, Nuclear Regulatory

Commission

(NRC) acting duty officer at their King of Prussia office in

Pennsylvania and

another BNL alumnus we knew from when he worked there called Schweller

but did

not request RAP assistance. Again, it was a notification, not a

request

for response.

By 8:45 AM the BNL RAP team and

equipment were ready to go if requested. Schweller and Meinhold called

Pennsylvania BRP to offer our assistance. The Coast Guard helicopter

stationed on Long Island was out of service so one was in route from Cape

Cod. Meanwhile, at TMI the teams from Met Ed and BRP had found 3 mR/hr

off site and an offsite sample from a Met ED team was reported as having a high

iodine level. By 9:00 AM a call from Schweller to Bores at NRC alerted

him to the availability of the Aerial Measuring System/Nuclear Emergency Search

Team (AMS/NEST) helicopter which could serve as a part of the RAP response or

as an independent DOE resource. At Andrews Air Force Base the AMS/NEST

team was readying their helicopter and equipment so that they would be

available if needed. Their initial notification had made its way through

many people and by the time it reached them they were told the accident was at

Nine Mile Island, a nonexistent reactor, so they collected topographic maps for

both Three Mile Island and Nine Mile Point Station just to be sure.

At about 11:00 AM Bores requested

the AMS/NEST helicopter for an aerial survey of radiation levels but did not

request the BNL RAP team. A few minutes later Meinhold called Maggie at

BRP and again asked if she wanted help. Possibly concerned because of

high iodine reading on the Met Ed sample that had just been reported to them,

she said "Alright Charlie, why don't you come on down." He interpreted that

as a request to send the BNL RAP Team. By early afternoon the BNL RAP

team was loading gear and personnel onto the helicopter and more gear and

personnel into vehicles. The AMS/NEST team was doing the same at their

base at Andrews.

At this point there were two separate

DOE responses being coordinated by DOE HQ in Washington: one was the AMS/NEST

team in support of NRC and the other BNL RAP working for Pennsylvania.

The Coast Guard

SH-3 Sea King rescue helicopter

On board the helicopter were 5

flight crew, Bob Friess DOE BAO, and 7 BNL RAP health physicists (HPs).

We had radiation survey instruments, the BNL Silver Gel iodine monitor, multichannel

analyzers (MCAs), electronics, sodium iodide (NaI) detectors and every

reference manual we thought we would need for calculating doses the public

might receive. That's me standing near the nose of the helicopter in the second

picture.

A second BNL RAP team was getting

ready to follow on by van with one health physicist and 3 HP techs carrying

more radiation measuring equipment and lead shielding for our counters.

The seating arrangements in the

helicopter were utilitarian and limited. Every seat available was used

including the jump seat between the pilots where one of our HPs rode. He

had strict instructions that the controls in front of him included the throttle

and he should keep his feet off of them. The rest of us were seated along

the sides in the back with no usable windows. Because of the noise

we were all given either headsets, over which we could hear the pilots'

communications, or simply hearing protection.

The pilot told us prior to takeoff

that we had done everything we could, to overload his

helicopter and had come very close to succeeding. So he would have to get

some forward speed before it would have much lift and with the wind direction,

that meant heading straight toward the Brookhaven water tower before we

rose.

We made it -- obviously

When we were more than half way to

TMI the pilots and our man on the jump seat could see a light plane headed

generally toward us. One of the pilots got on the radio to a controller

on the ground and asked them to try to contact that plane and get it out of our

flight path. Radio communication with light planes is not guaranteed, but

he was reassured when it changed direction. Then, for some reason, that

plane turned directly toward us. According to those who could monitor

what was said, the pilot used language that was stronger than the usual reserved

tones you hear on a commercial flight. At the same time we banked and

dropped about 1000 feet. For me, not having a headset and therefore having

no idea what was going on, it was a lot like a roller coaster ride, but the

faces of those across from me who had heard the pilot went white.

As we approached TMI a warning light

alerted the pilots to a crack in one of the rotor blades. This is a

situation that requires the pilot land as soon as possible. But as he was

about to pick an interstate median or a farmer's field the light went

out. He figured it was just an instrumentation problem.

The location that the pilot had been

told was our destination in Harrisburg was a landing pad at a hospital.

It was designed for much smaller helicopters so he chose not to land there and

instead proceeded to the general aviation Harrisburg Capital City Airport about

7 miles upstream of the TMI plant.

When we were on the ground we

noticed that the AMS helicopter had also arrived but we did little more than

wave to them. After landing, our first order of business was to survey

the helicopter to determine if we had picked up any contamination on our

approach. While clambering around on the helicopter one of our team

noticed that each of the rotor blades had a small radioactive source, and there

was what appeared to be a Geiger tube on the body of the helicopter. We

asked one of the crew and he told us that each blade is hollow and pressurized

with gas, and if a crack develops the pressure bleeds off and the source moves

to an unshielded position. The blade failure light problem was

explained! We had flown close enough to the reactor for the radiation

from it to trip the warning light.

None of us had thought to have an

instrument running as we were approaching. Another lesson we learned that

day.

Wednesday evening we set up shop at

the BRP offices in Harrisburg. Most of us went out to try to find the

plume or whatever may have been deposited from it. To figure out where to

search, we used a newspaper weather map and flags that we saw as we drove

along. A couple of others of our team set up the multichannel analyzers

at BRP and started with dose assessments using measurements and samples that

had been collected by BRP and Met Ed staff. At this time the high sample

that had been taken earlier was recounted and no iodine was found.

For the field teams, radio

communication was limited to rare instances when we were close to the BRP

offices or had favorable geography. Mostly we relied on finding a pay

phone and calling in our measurements of beta and gamma, the number of air,

soil, water, and vegetation samples we had collected, and the locations of the

measurements and samples. That worked early in the evening, but many of

the phones were inside businesses which closed later that night so we were

often getting data that we were unable to report. Communication from BRP

to us would have been useful too if they had been told about a release or

change in wind direction. With what we had that night, it wasn't going to

happen.

There were occasions we asked

ourselves, "Are we lost?"

It would have been good to know the

territory, but we didn't.

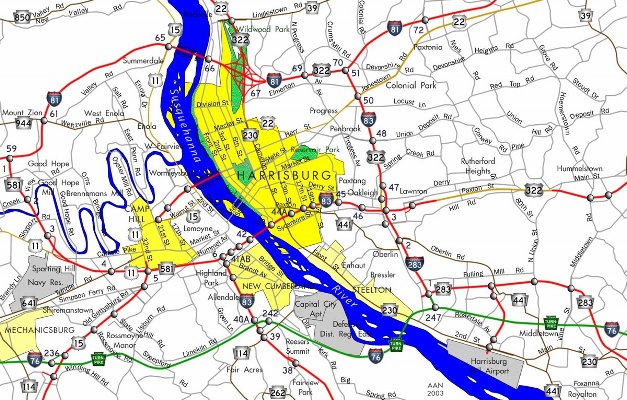

Maps of the area

We

were using gas station maps similar to the ones shown here. If we were

lucky we would be sampling where all the local roads were shown like on the

first map. But often we were working in areas outside the metropolitan

Harrisburg inset map where there was a much lower level of detail so we had to

use geographic interpolation, in other words, guess. Here are a few

points on the map that may help to orient you. BRP was located in the

center of Harrisburg a couple of blocks from the river. Capital City

Airport where we landed was across the river to the south east.

Harrisburg International Airport, the area's main airport, and Middletown,

where media, NRC, and other agencies would set up their Trailer City on

Thursday, are further in the same direction but on the east side of the river.

TMI (shown on the second map) is down river a mile or two to the south east.

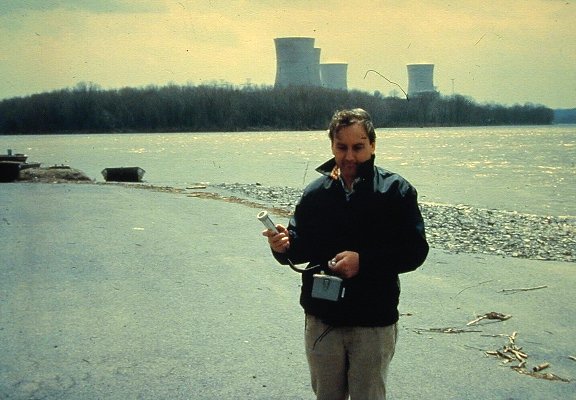

About midnight two of us were

driving on a back road a few miles from the plant. We had learned our

lesson from the flight and had a Geiger counter running on the seat between

us. It was making the typical background clicks. Then rather abruptly

the counts ramped up until there were so many clicks they sounded like a

hiss. That caught our attention. It didn't hurt that a couple of

minutes later a fire siren sounded. Had a major release occurred and they

were trying everything to notify the public to evacuate? It was

unrelated, but we didn't know that at the time so our imaginations ran

wild. We had found the plume. It was only a few mR/hr but it's not

what we expected after several hours of surveying and finding little or

nothing. We got out and connected the Silver Gel sampler that had been

developed at Brookhaven about a year before. This provided its first real

test.

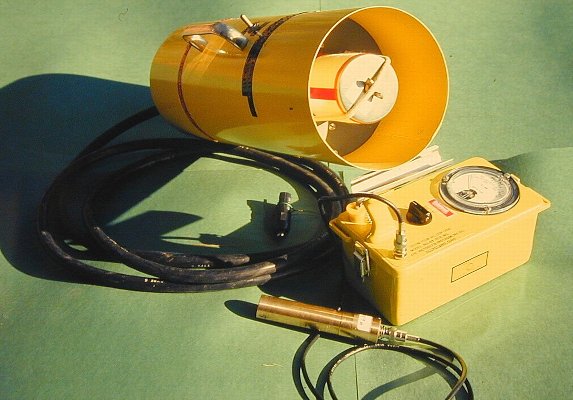

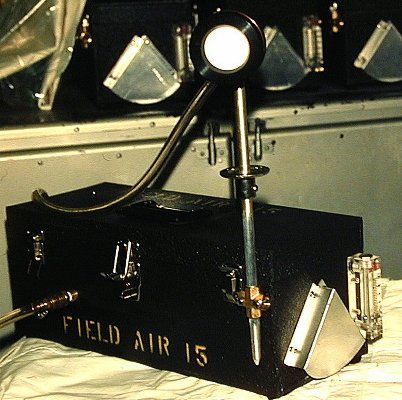

Brookhaven Silver Gel plume sampler

NUREG/CR-0314 BNL NUREG_50881

The Silver Gel sampler was designed

to capture inorganic and organic iodine by chemically binding it in silver

loaded silica gel. Noble gases had a very low absorption rate on the

gel. This means that the sampling process did a good job of

discriminating against them making it easier to measure low iodine

concentrations in a mixed plume. The discrimination was further enhanced

by a bismuth screen in the Geiger tube that enhanced its sensitivity to the

iodine with respect to the noble gas counts. It was adaptable with dual

motor windings so a simple plug would let it run on either 12V from a car or

120V line voltage. It had a preset 5 CFM flow rate so no adjustments were

needed in the field. All we had to do was sample for 5 minutes and take

the sample out of the plume, flush it with uncontaminated air, put the GM probe

into the center of the filter cartridge, take a count, peel off the filter

paper, take another count, then check background with a clean filter.

With those counts we had a fairly sensitive measure of thyroid

dose. Depending on the time after shutdown, duration of exposure, and the

age of the exposed individual, doses of a fraction of a rem to the thyroid

could be determined in the field. Our first sample did not indicate any

iodine. We also collected samples on charcoal filters as a backup.

After taking samples at a few more

locations in the plume we made our way back to the BRH offices in Harrisburg

where we counted them using a sodium iodide detector and multichannel analyzer

to enhance sensitivity as much as we could

The time was now pushing 4:00

AM. You probably have never have had the challenge of hand analysis of

such a spectra, with lousy statistics in every channel, when the result could

influence the state's decision on a major evacuation, all of this while you are

significantly sleep deprived.

Our discussion could best be

described as interesting. We then recounted what appeared to be the

highest samples for longer and looked again. We concluded that we had not

found iodine in any of the environmental samples. But based on the noble

gas on the charcoal filters we had definitely collected in the plume not just

under it. Our next priority was to find a bed.

.

AMS/NEST

helicopters

Earlier that day we had left the

AMS/NEST Andrews team at the Capital City Airport. They had started

making monitoring flights that afternoon and planning for a continuing presence

there. So they found unused offices and work spaces in one of the

hangers, had multiple phone lines installed, and set up a command center.

The first picture is the first helicopter dispatched from Andrews. The

second shows the larger one which had been on another mission and arrived later

as did still more AMS/NEST staff. A team from Bettis Atomic Power Lab

arrived from Pittsburgh. They established their base at Capital City

Airport with the Andrews group ready to sample and count.

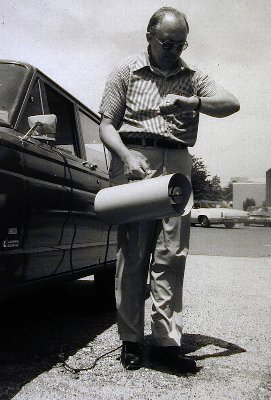

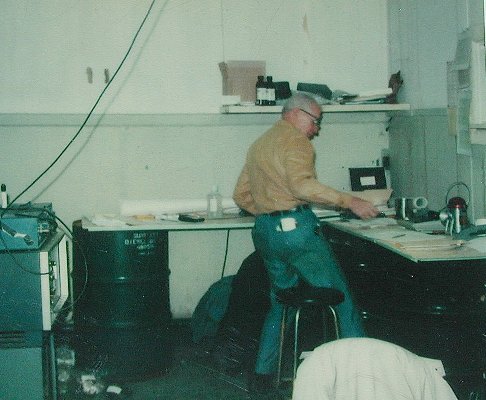

Three members of

the BNL RAP sampling team

The second BNL RAP contingent had arrived Wednesday evening. All the teams taking measurements had the problem of distinguishing among several possibilities. Was there a plume overhead, or were they immersed in the plume, or looking at ground deposition?

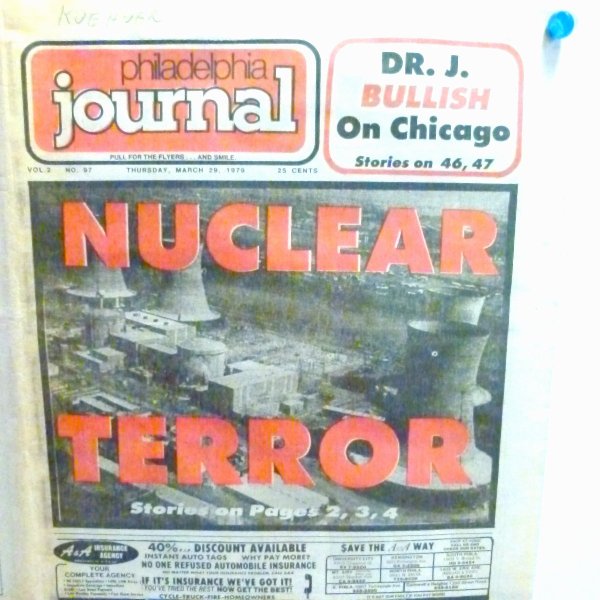

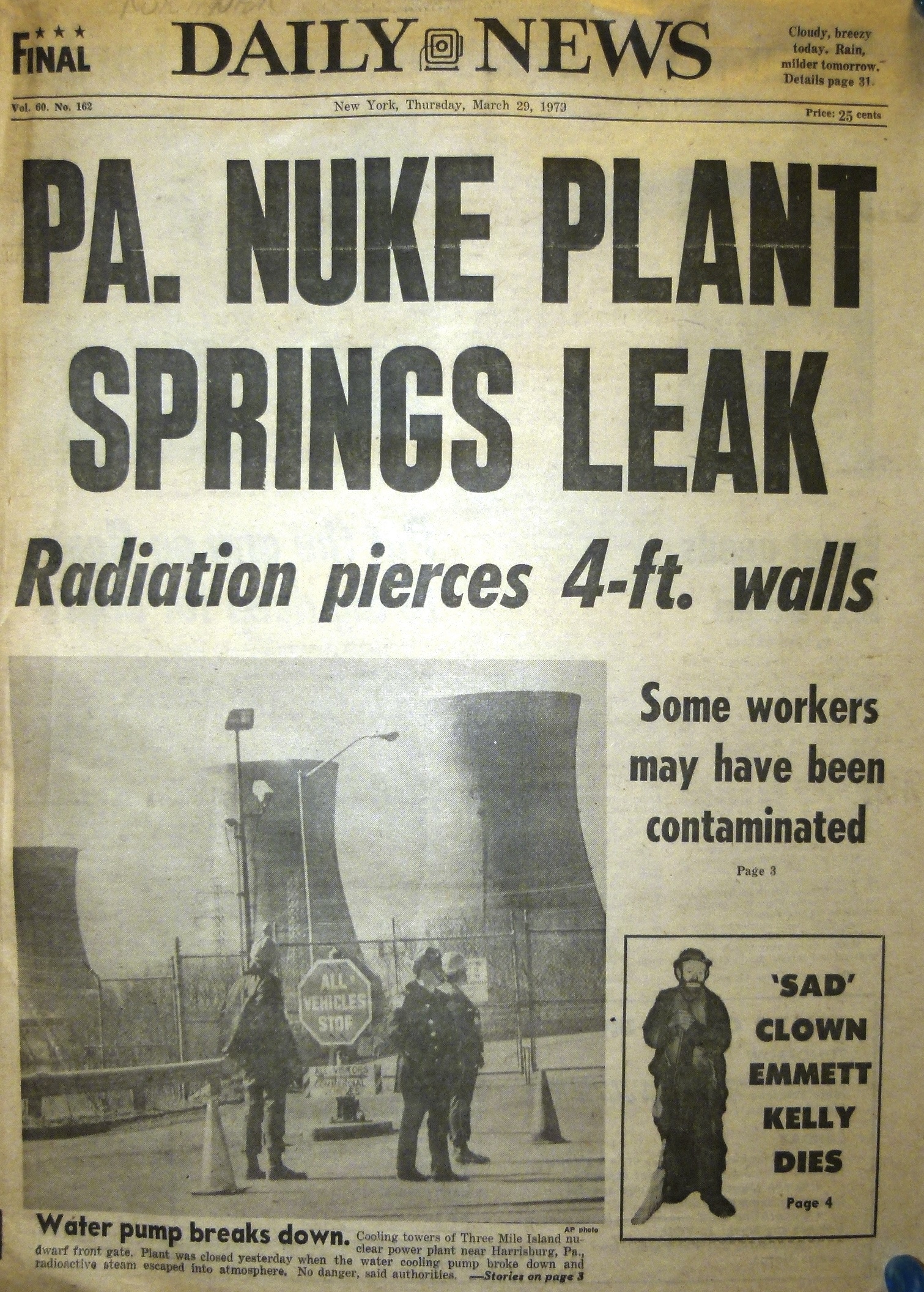

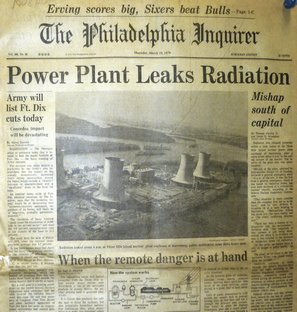

On

Thursday morning this was one of the front pages that the country was greeted

with. Not exactly what was needed to reassure the public that the only

radioactive materials that had been detected outside the plant were noble gases

with very low public dose.

Radiation

piercing 4 foot thick walls and a nuke plant spewing radiation seems overly

dramatic though not as bad as the previous front page. To add to the

public's perception of what was going on, the movie, The China Syndrome had

been released just 12 days before. That movie has a line that the accident

that they were dealing with could "contaminate an area the size of

Pennsylvania." It isn't a bad movie if you can avoid getting hung up on

some errors in technical details about plant operation.

The New York Times and Philadelphia Inquirer front pages

Not

all of the reports were as outrageous. The New York Times had their story

about TMI above the fold, but other stories were given bigger headlines and

more prominent placement on the page. The Philadelphia Inquirer had a

less moderate take but not excessively scary.

As

with cable news and the internet today you need to pay attention to the

source.

On

Thursday the teams from Bettis were on scene, teams from Knolls Atomic Power

Lab in Schenectady, NY on the way, and more AMS/NEST personnel and equipment

coming from Las Vegas, Monitoring was well covered. So far noble gas but

no iodine or cesium had been detected in any of the field samples and the

off-site radiation levels were low. So I, along with the rest of BNL's

first RAP team got a chance to catch up on overdue

sleep, worked a little more, and then DOE BAO decided we weren't needed,

so we headed back to Long Island. BNL's second team left the area on

Friday morning.

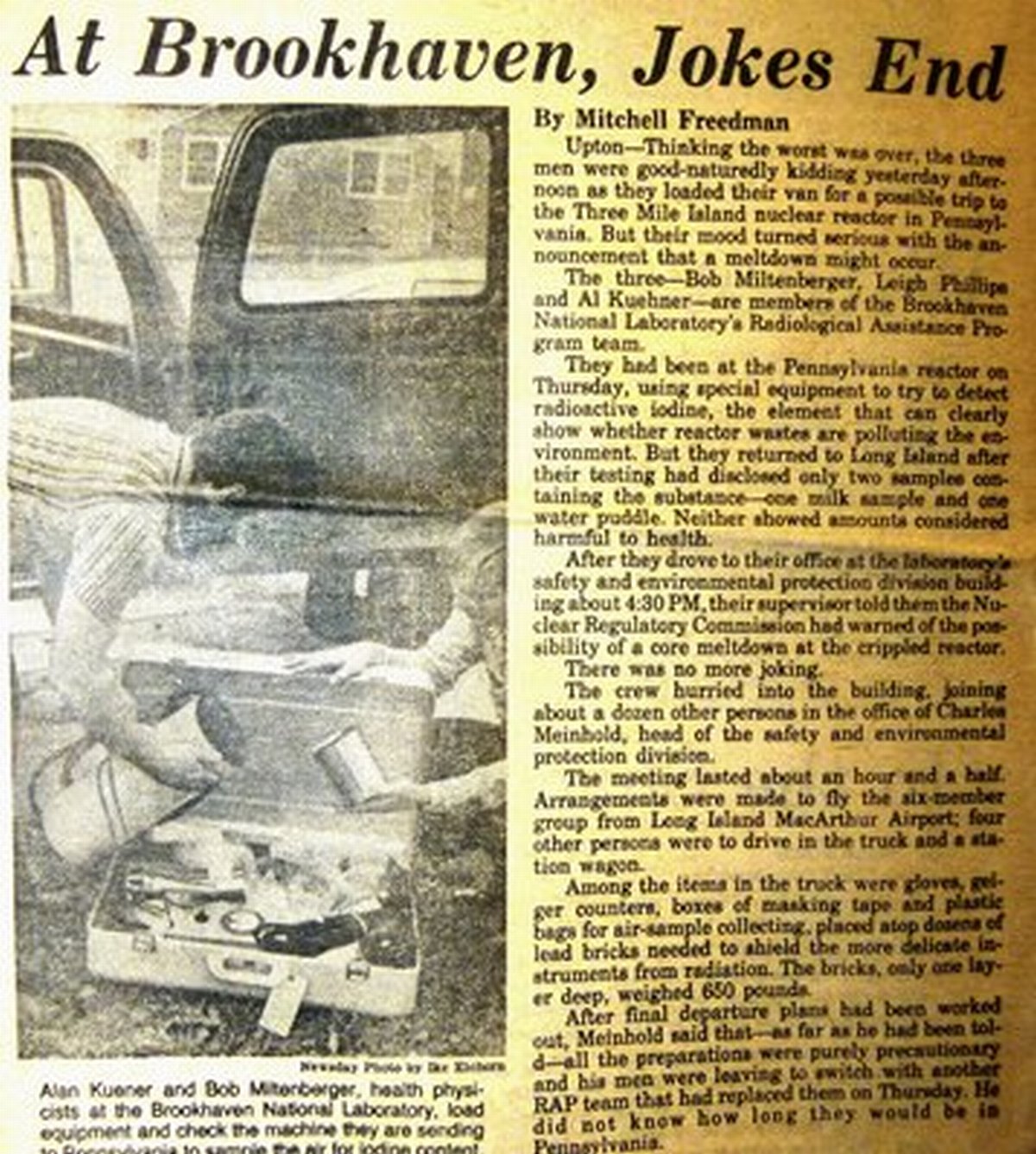

Newsday article

on Saturday

On Friday I was back at BNL with

most of the rest of the first team that had been deployed, reloading our kits

with fresh Silver Gel sampling media and other supplies that had been

depleted. A reporter from the Long Island paper, Newsday, was there

with us while he was waiting for official statements from BNL and DOE BAO to be

prepared. We were not authorized to speak on the record about our

response but we took the opportunity to "teach" the reporter about Curies,

rads, reactors, and answer general questions while he was waiting for the official

news release. Our explanations seem to have been useful if you look at

his later reporting.

My recommendation is to teach

whenever you can. If you are in some emergency response field and have

the opportunity, befriend someone in the media now, so they will have you as a

trusted source for background information about some future incident or an

explanation of a technical point when they need it. Many of them will

appreciate it.

While we were talking to the

reporter and apparently in a light hearted mood we got the word that we were

going back to TMI and we got serious. This time we went by van with

counting equipment and 600 pounds of lead brick shielding for our detectors.

The reason for our abrupt turnaround and the headline, was that earlier in the

day a Met Ed helicopter flight had measured 1200 mRem over the Vent Stack

during a planned release. However, when the report of that measurement

reached Washington, the critical information about the location and timing of

the reading had been lost. Somehow it was interpreted as being at ground

level in Goldsboro, across the river from TMI.

I would offer a corollary: The

further news travels the more verification it requires. That applies equally to

its travel from place to place or through organizational levels.

There seems to be an

inverse relationship between the distance information travels and its relation

to the actual facts. Inverse Square perhaps?

Later Friday morning concern

developed in Washington that there was significant core damage and that a

hydrogen bubble had developed in the reactor that contained 1000 cubic feet of

hydrogen. One comment from an NRC Washington "expert" was that it was "A

failure mode that has never been studied. It is just unbelievable."

At the report of significant core

damage one of my coworkers asked "Could the fuel fall down into a heap at the

bottom of the vessel?"

My reply "It would be critical if it

fell into a pile", both puns intended.

Should an evacuation be ordered?

At the NRC in Washington, they were

basing their decision on the erroneous 1200 mRem reading and various officials

recommended evacuation to 10 miles downwind, or 10 miles all around, or maybe

just 5 miles. At the BRP in Harrisburg they had accurate info on that

reading and they told Governor Thornburgh that evacuation was not necessary.

NRC Commissioner Hendrie recommended

to the Governor a partial evacuation to 5 miles. President Carter told

the Governor "Err on the side of safety and caution." At his midday press

conference the Governor said "Pregnant women and preschool children within 5

miles should leave the area." The exodus began for those specified and many

others and continued through the next several days as the press continued to

report fears not facts.

A DOE contingency plan was in place

in case the situation at the reactor looked like a major release was

possible. An alternate facility had been identified at an Army

Post in

Carlisle, PA 25 miles upwind. Our instructions were to grab

essential

equipment, data, and go. With teams out collecting samples it was

necessary to have a code word that could be put out over the radio net

that was

now active courtesy of Los Vegas AMS/NEST. The code for

relocation was "Jim Thorpe." We were told it was because he grew

up in Carlisle but we knew

that it was really because he had been known as the world's greatest

athlete

and he could run.

My recommendation to those of you

who are planning for your next response "Have plans B, C, and D ready well

before you need them."

It was a dark and stormy

night. Actually it was drizzly and foggy but I can't resist the

cliche. It was after midnight and several of us were counting samples

that had been collected during the day. The routine was to count for 7

minutes, use a teletype to print out and punch paper tape for the part of the

spectra that would include the iodine peak if any, then look for any indication

of an actual peak and recount longer if we saw one, load a new sample and

repeat. We had settled down in our routine when a damsel in distress

appeared at our door.

The young lady had been dropped off

at the airport planning to pick up a Jeep that her dad had left there earlier

in the day. She intended to use it to evacuate but it wouldn't start and

she was scared. We had a few minutes between samples and she was nearly

in tears so there was no question, we were going to help if we could.

Several of us went out, opened the hood while one of us turned the key.

She and the rest of us were looking under the hood and saw a purple blue glow

appear over the engine.

She was sure it was radiation!

We recognized that moisture and the ignition wires were the problem. We

pulled them and took them inside to clean and dry them. Time to change

the sample. Reinstall the wires. There was an improvement but it

was still a long way from running well. Clean and dry the distributor

cap. Not right yet. Change the sample again.

Check the ignition wires

resistance. Some are much higher than others. Change the

sample. The high resistance was traced to the connection at the metal

tips on the wires. Once that was understood all we needed to do was

remove the tip, clip a half inch or so off the wire, and replace it.

Changing samples as needed. All the time we were doing this we were

talking to her about what we were doing and what we had found, both with the

Jeep and the environment. When the Jeep was running well we said goodbye

and sent her on her way.

We thought that was the happy ending

that we had been working toward but we were in for a surprise. About two

hours later she was back with coffee and donuts for us. I have no idea

where she had to go to get them at that hour of the night but she was now

comfortable enough with what was going on to do that for us.

Your actions can speak volumes.

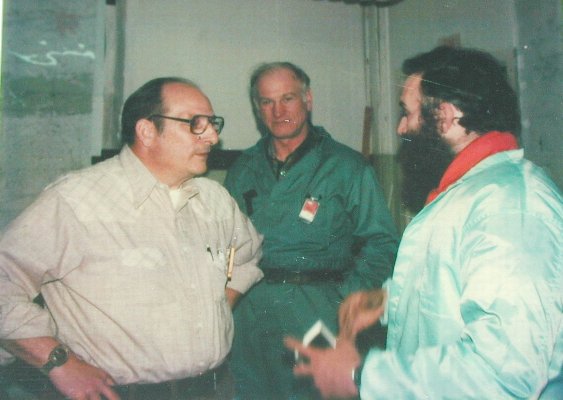

Press corps at Middletown

Saturday NRC, Met Ed, and the

world's media are at Middletown, across the river and much closer to TMI than

the DOE operation.

The entire DOE operation was at the

Capital City Airport. The press didn't know about us or the scope of our

monitoring effort.

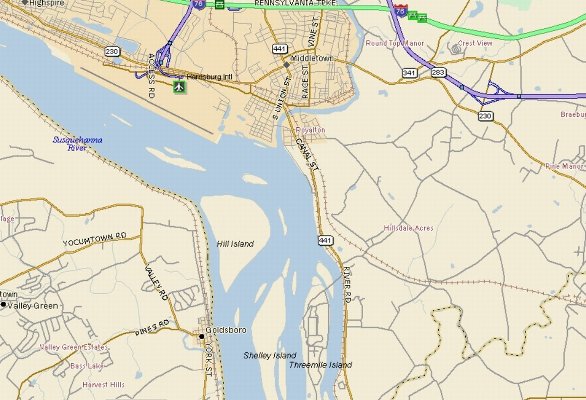

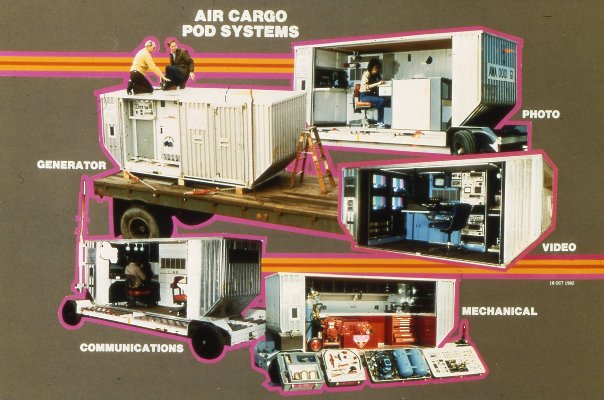

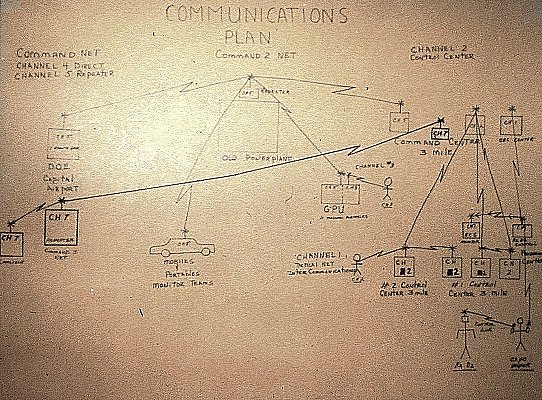

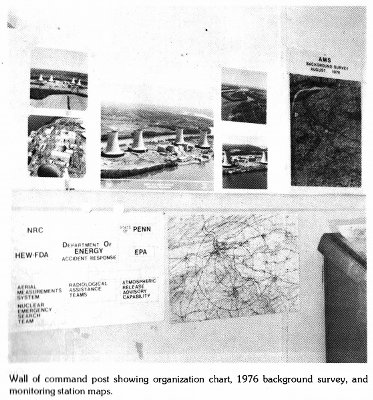

Map of the area and AMS/NEST resources

The radio net diagram and status board at the command center

By this time AMS/NEST Las Vegas was fully involved with photo and video pods on site. A radio network with repeaters had been installed; data plots, assignments, and maps were all readily available, as was data from the Atmospheric Release Advisory Center (ARAC) at Livermore. The data was provided by phone and fax until a remote terminal was delivered and set up.

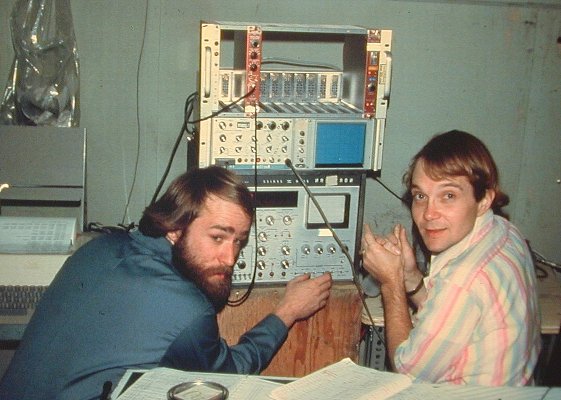

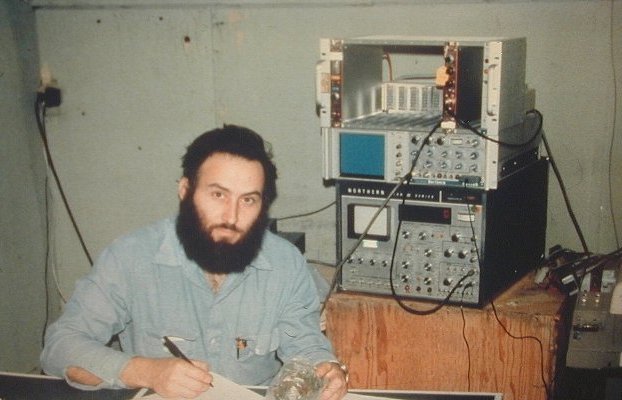

DOE dose assessment group

The DOE dose assessment group was made up of experts from throughout DOE. They were using flight and ground survey data, ARAC information, meteorology, State measurements, and TLD stations. Their work table was a piece of plywood on sawhorses, paper references were scattered about, a handheld radio and phone for communication, and not a computer anywhere to be seen. By this time the analyzed output was going to State, NRC, and Met Ed.

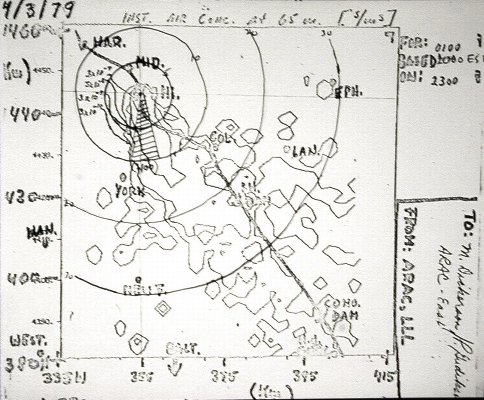

ARAC plot with

annotations

Here is an ARAC plot updated

with some of their notations. Something that strikes me when looking at

this plot is that the world is lumpy. You can't possibly get enough data

to model all of that lumpiness. When pressed, the folks responsible for

those models admitted there isn't a good reason to expect that any particular

bubble that is shown on this map is actually where the model predicted. However,

the maps do provide a good estimate of the scale and magnitude of the

variations to be expected.

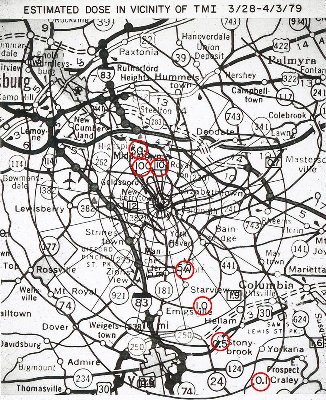

Dose assessment

output

This is one example of the many dose

assessments they produced

About 3:00 AM Sunday morning a call

came in to the command center. It was down the hall from where I was

working and it kept ringing. Since I was about the only person available

at that hour I answered it

It was from the Whitehouse!

A staffer was preparing a briefing

for President Carter prior to his visit scheduled for later that day. I

didn't have the answers needed so I called Andy Hull who by many, was

considered to have the best grasp of the total dose picture. He had the

current information that was required and could interpret it for them.

My takeaway from that was "If

you don't know, admit it, and find someone who does."

My usual jobs for the remainder of

the response were to collect representative samples starting in the afternoon

then package and count them, looking for any iodine, continuing late into the

night. Then prepare a report of what was found for the dose assessment

group. It should be noted that nonstandard samples may be useful. A

sample from a puddle or a ditch by a road may increase detection sensitivity

because it has collected from a large area and so can be useful even though you

won't be able to use it to compute a population dose. They can be used to

confirm that something more than noble gases is getting out of the plant.

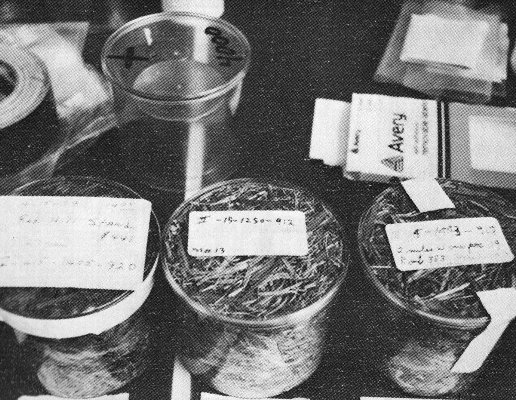

Some

environmental samples

Here are some of our vegetation

samples in Marinelli beakers labeled and ready for counting.

Sample counting facilities

Our

work area was similar to what the dose assessors were using, with our analyzers and teletypes on work benches made

from boards and 55 gallon drums or packing crates with teletypes for readout.

That's me in the third picture.

Our

usual attire when collecting samples didn't let us travel unnoticed. It

was effective in keeping us warm, reasonably dry, and clean but it tended to

attract attention when we were out. On one sample collecting foray, I

made a quick stop at my motel to pick up something. As I was jogging back to the car a small

group of people saw me and were sure I was running because of radiation. Seeing

their reaction I stopped to explain that I was one of a team that had been

there to measure radiation since the first day of the accident, and that we

hadn't found anything to be alarmed about. I also explained that I was

rushing because I was late not for any other reason.

Keep in mind that whatever you are doing your actions can be misinterpreted.

State police provided transportation

The

Pennsylvania State Police training barracks is located in Hershey not far from

TMI so officers were pressed into service as drivers for sample

collection. This had a couple of advantages. First, they knew the

roads so we didn't have to figure out where we were, and second, we could be

labeling samples and writing our logs while we were getting to the next

location, saving some time. Each sampling team would be given roads to

cover. Every half mile we would collect vegetation and soil samples, take

gamma and beta readings, and grab water samples whenever we passed a stream or

pond. While I was doing this my driver noticed that we had someone

tailing us. He would stop when we did, and observe what we were

doing. Obviously a reporter, but this time I wasn't inclined to be

helpful.

The officer asked "Do you want to lose him?"

My

reply, "YES!"

And we were off on a ride that rivaled the one in the helicopter. You probably already know that you should be careful what you say to an officer.

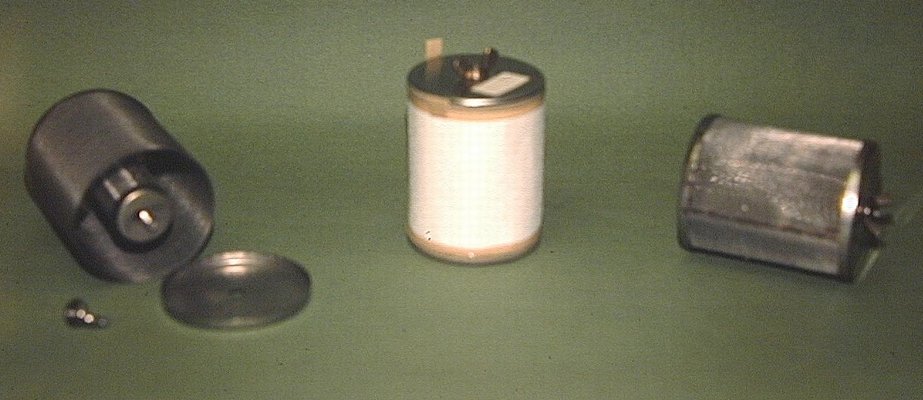

Brookhaven

continuous air sampler

One

day my assignment included air sampling. This time I was using another

BNL developed sampler, pictured here. It was intended to sample at a

lower rate for a longer time. It required 120 V power so several had been

set up at fire and police departments, churches, schools, and other public

facilities. For those I just needed to verify the flow rate, change the

sample cartridge and record the time. There was one site directly across the

river from the plant, south of Goldsboro. We would sample it occasionally

and whenever we had been alerted to a planned release. Because it wasn't

near any public source of power, we would set up a small generator, plug it in

and let it run as required. When I was setting up I noticed two farmers

watching from a porch a few hundred feet away, so I went over to talk to them

while it ran. In the course of our discussion I asked them if they

weren't concerned since they were so close to the reactor. One of them

replied that based on what I was doing he figured that I probably knew if it

was dangerous to be there, and I hadn't left so they didn't see any reason to

either.

Again, what you do can be far more important than what you say.

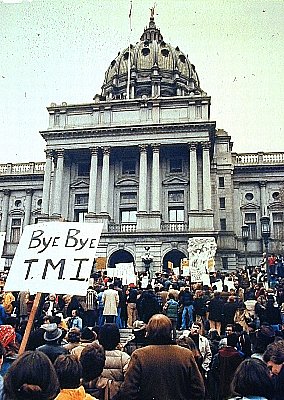

Harrisburg protests

These pictures, taken at a protest in Harrisburg, will give you a sense of the local reaction. And in Washington outside the church President Carter attended was a sign "Stop the merchants of Atomic Death." Fortunately I was spared any direct contact with these folks.

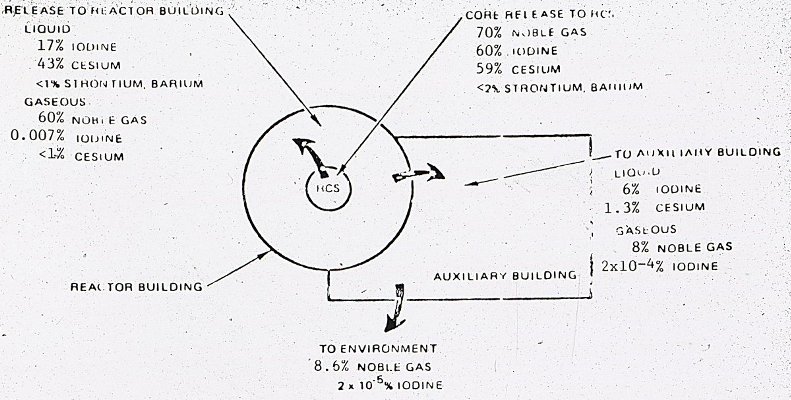

Iodine

and noble gas pathway to the environment

You may be wondering where the iodine went. With failed fuel you would expect it to be released. This diagram shows the principal parts of the path from the core to the environment. From the fuel elements in the reactor some of the iodine went to the coolant and from there through the PORV (here called the safety valve). The tank intended to catch the coolant overflowed onto the containment floor. From there some of the coolant was pumped into the auxiliary building. Some of the gases that had been dissolved in the coolant exchanged with the building air and went up the vent stack.

Core inventory

to environment fractions

This diagram is based on a very much later analysis. It shows the percentage of the inventory

of radioactive materials in the core

that made it

through each of these steps from fuel to the environment. The table

below

summarizes the fractions. It is apparent that the tendency of

iodine to remain dissolved in the water released from the reactor

vessel prevented a much larger environmental release. This

resulted in much lower public dose than had been assumed prior to that

time.

|

|

Strontium, Barium |

Cesium |

Iodine |

Fraction of the iodine released from the liquid |

Noble gases |

|

Core to reactor coolant |

< 2 |

59 |

60 |

|

70 |

|

To containment building in the liquid |

< 1 |

43 |

17 |

|

|

|

To containment building as a gas |

|

< 1 |

0.007 |

4x10-4 |

60 |

|

To auxiliary building in liquid phase |

|

1.3 |

6 |

|

|

|

To auxiliary building as a gas |

|

|

2x10-4 |

7x10-5 |

8 |

|

To the environment as a gas |

|

|

2x10-5 |

|

8.6 |

Percent of core

inventory released to various compartments

Walter

Cronkite at the time was known as the most trusted man in America. His

comments over the first three days of the accident: On Wednesday "The

start of a nuclear nightmare." Thursday "There's more heat than light in

the confusion surrounding the incident." I certainly agree with that

one. On Friday he talked about Prometheus, Frankenstein, and "Tampering

with natural forces."

He

wasn't helping to calm the public's concern.

Newsweek, Time and more news articles can be found at this link.

Here is a quick summary of things I

learned or found useful during my response to TMI:

Know your team well.

Don't be reluctant to ask for

help.

Prepare for contingencies.

Have plans B, C, and D ready before they are needed.

Know where you are going both

geographically and logically.

Know and trust your instruments and

the resources you have available.

The media can be your friend, or

not.

Teach whenever you can.

The further information travels

through the organization the more verification is required.

Your actions can be much more

important than your words.

Recognize that you can't get enough

data to completely model the world.

Politics trumps science every

time.

Have staff available to run 24/7 for

as long as required.

If you don't know something, admit

it, and find someone who does.

You may be the only one who knows

some fact, share it.

The time line and some of the quotes are from "Crisis Contained, The Department of Energy at Three Mile Island, A History, December 1980"

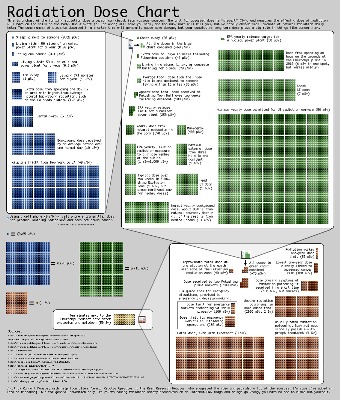

A couple of things you may find useful as training aids when explaining radiation effect to members of the general public.

For a good

graphic showing the relative size of radiation doses and their effects: https://xkcd.com/radiation/

Go to our Science Fun page

Go to our Travels page

Go to our Personal home page

Go to our Community page

E-mail Nancy and Alan

Science Fun, Inc. is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation.

If you would like to help us here in Eastern Kentucky please send a note to us or click on the button below and select an amount.